Last year I developed a strong attraction to Joe Pesci. I had never thought twice about him before, and that was part of why he suddenly appealed to me. Watching Pesci onscreen has always left me feeling pleasantly empty: no persona to pull apart, no unslakable longings to carry. And mid-lockdown this is exactly what I wanted — to absent myself and enjoy people the way I enjoy other animals, as living things, simply being whatever they are.

My relationship with Joe Pesci has always been one of disinterest. Mine, and imaginatively, his. Seeing Home Alone as a child, what stood out most for me was the fact that his character didn’t care about children. In movies for kids, adults can be malicious or kind, but they always care; they’re meant to reassure young viewers that kids are the center of the universe. But Pesci’s burglar didn’t care about Macaulay Culkin. He cared about taking his family’s stuff. Disinterest, in this context, was more jarring to me than outright hatred, though it made him more assimilable. I never developed any conflicted attachments.

Pesci’s appeal comes without strings attached. It’s a service to his audience. You can enjoy him with no disappointment when his character is killed off. These characters have drives, but not appetites: they are feral animals, more volatile, but somehow more safe, because their impulses are entirely legible. My attraction to Joe Pesci was satisfyingly dry: a little compulsive, but free of the desire for things I don’t want. I can’t think of many villains less eroticized than his.

****

At his coldest, there is a weightlessness to Joe Pesci that is mesmerizing. He rants with a natural rhythm — many of his most famous lines were improvised — and his voice, while heliumized, seems to glide from one side of his mouth to the other like smoke. He inflicts violence with slapstick agility, exhibiting the sort of control that comes easiest when a skill is automatic — “if you learn how to do comedy at a young age, it creeps into everything you do,” he once told Empire magazine — and when you’ve already given up.

Pesci never chose to be an actor. He was groomed for the stage by his father, Angelo, who worked three jobs, driving forklifts and tending bar, to pay for his son’s training. “My father loved me so much that he did not want me to be a laborer or anything,” Joe told the New York Times in 1992. “I don’t know if it’s the right thing to do — push your kids into something and then stay on them until they do it.” From the age of four or five, he was appearing in plays in New York City and on TV variety shows. “I guess it’s like if you train a puppy he gets these rewards,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1991. “You learn to get the reward of the audience.” Stage kids, he added, “feel very unloved. If things don’t go right in their life they’re always trying to please people.” Pesci would grind away in show business for the next three decades. By the time his big break arrived, he’d almost completely retired his hopes.

In a famous David Letterman appearance from 1994, Pesci plays the role his fans had come to love, with the expected sprezzatura: letting curse words slip, hopping in and out of his seat with cartoon menace, and brandishing a cigar, a regular prop in his late-night appearances through the decade. It looks so natural in his hands that one would assume he’d been smoking for most of his life. In fact, he’d picked up the habit just two years earlier, preparing for his leading role in The Public Eye.

****

The designation of “character actor” has always struck me as paradoxical: never the protagonist, but forever recognizable as oneself. Pesci is a character actor, perhaps the most famous living character actor, but for a brief window in the early 1990s, there was a push to make him a bankable leading man. The more famous attempt, My Cousin Vinny, was a critical and commercial success, but it didn’t sell him as a romantic lead. By playing against type — good neighborhood guy, versus bad neighborhood guy — he only reinforced the type; and the pairing of 49-year-old Pesci, pint-sized and relatively brined, with the pert, 27-year-old Marisa Tomei was a bit of a visual gag.

The Public Eye came out later that year, to less fanfare: a tight, stylish little neo-noir that is good, as opposed to just alright, thanks to the pathos of its star. Pesci plays a crime photographer, Leon “Bernzy” Bernstein (modeled after the iconic New York City photographer Arthur “Weegee” Fellig), who falls for a rich nightclub owner named Kay Levitz (Barbara Hershey) after she seeks his help in fending off the mob. The physical and social contrast between them is stark, but not meant to be funny. She’s beautiful, glamorous and sleek; he is short, balding and grubby. We know him to be a true artist — eventually Kay does, too — but his confidence ends with his work. Bernzy never convinces himself that he could “win” Kay, and he never convinces us, either. They don’t get together in the end. They barely even touch. “You expect him to rip into her when he gets the opportunity,” Pesci told Roger Ebert, “but he doesn’t even know how to hold someone. When he had the opportunity, he didn’t know where to put his arms and hold and kiss her.”

The film had a budget of 15 million. It grossed just over three. Pesci’s devotion to Hershey is moving in its hopelessness, but unsatisfying. We end up feeling sorry for him, which is the worst way to feel about a hero. If Pesci had been taller, more conventionally handsome, his characters’ failures might have been easier to bear — characters who lose in love aren’t losers if we desire them. Had he injected some arrogance or swagger into the role — had he been less willing to appear so weak — his performance would have been easier to metabolize, then forget. Instead, Pesci as Bernzy is impaired by his own gentle nature. He is the hapless little man that his gangster characters violently repudiate.

I watched the film in a warm state of shock, the happy astonishment of watching a friend exceed themselves, and formed two major impressions: That Pesci was exquisite; and that most filmgoers, myself included sometimes, would rather watch a man pop another man’s eye out with a vise than be emasculated.

****

If in some bar trivia game I’d been asked to name Pesci’s heroes, I might have said Frank Sinatra, or Marlon Brando, some mid-20th-century icon of white masculinity. I would assume, rightly or wrongly, that he’d grown up fearing and admiring the sorts of men he’d go on to play. (I tried not to think too much about that, when I thought about Pesci, the same way I say I love James Gandolfini, not Tony Soprano.) But as a teenager, maturing into his own tastes, Pesci’s main interest was jazz, of which his hometown of Newark was an epicenter, and his idol was a Black American singer named Little Jimmy Scott.

Jimmy Scott is now considered one of the most influential jazz vocalists of the last century. Back then he was a local legend, whose illustrious admirers included Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, and Ruth Brown. Scott was known for his slow, expansive phrasing and the romantic agony in his voice, as well as his striking sound and appearance: then in his early 30s, he stood at 4’11’ (he would soon grow several inches) and sang in an alto range. He was often mistaken for a woman or a little boy.

Scott’s physical slightness was caused by Kallmann syndrome, a genetic condition that prevented the onset of puberty. He’d been diagnosed at the age of 13; that same year, his mother, with whom he’d been very close, was killed by a drunk driver while pushing his sister out of the car’s path. Jimmy and his nine siblings were separated in the aftermath and dispersed across different homes. For the rest of his life he would long to get the family back together and to start one of his own. But his relationships were often disappointing and sometimes outright abusive, with Scott bearing the brunt of the aggression.

As a performer, Scott seemed to dwell in perpetual, beatific heartbreak. “I believe sensitivity is the key,” Ruth Brown told his biographer, David Ritz. “He wasn’t a little boy, he wasn’t a grown man, but you knew he’d lived other lives and suffered in ways we could never understand. That suffering, in a person so petite and tender, made a mighty impression.” As Scott told Ritz, “Early on, I saw my suffering as my salvation. Once I knew that, I understood God had put me in this strange little package for a reason. All I needed was the courage to be me. That courage took a lifetime to develop.”

Pesci was around 14 when he first saw Scott perform, at the Front Room in Newark’s Third Ward. “The sound of his voice turned my world upside-down,” he told Ritz. “All the magic, all the mystery of grown-up life, was in his voice. He gave jazz a twist — an individual turn — I’d never heard before. I related in every way. Just as he was called Little Jimmy, they were calling me Little Joe.” Pesci approached him and the two struck up a friendship. He would follow Scott around, trying to make himself useful, and Scott would become his mentor. “We’d sing together nonstop for hours, sometimes all night,” Pesci said. “He’d teach me phrasing and harmony. He’d teach me songs I still remember.” Pesci dropped out of school to pursue music. “All I wanted to do was sing like Jimmy Scott.”

Through the late 1950s and ’60s, Pesci would sing in road-stop taverns and in nightclubs around the Tri-State Area. He would play in a jazz quartet with a young songwriter named Bob Gaudio, whom he’d introduce to his childhood acquaintance Frankie Valli. Bob and Frankie would go on to form the Four Seasons, one of the most popular groups of the 1960s, while Pesci played in the touring band for somewhat less popular Joey Dee and the Starliters. Between gigs, he joined the civil service and worked a series of day jobs, delivering mail and cutting hair.

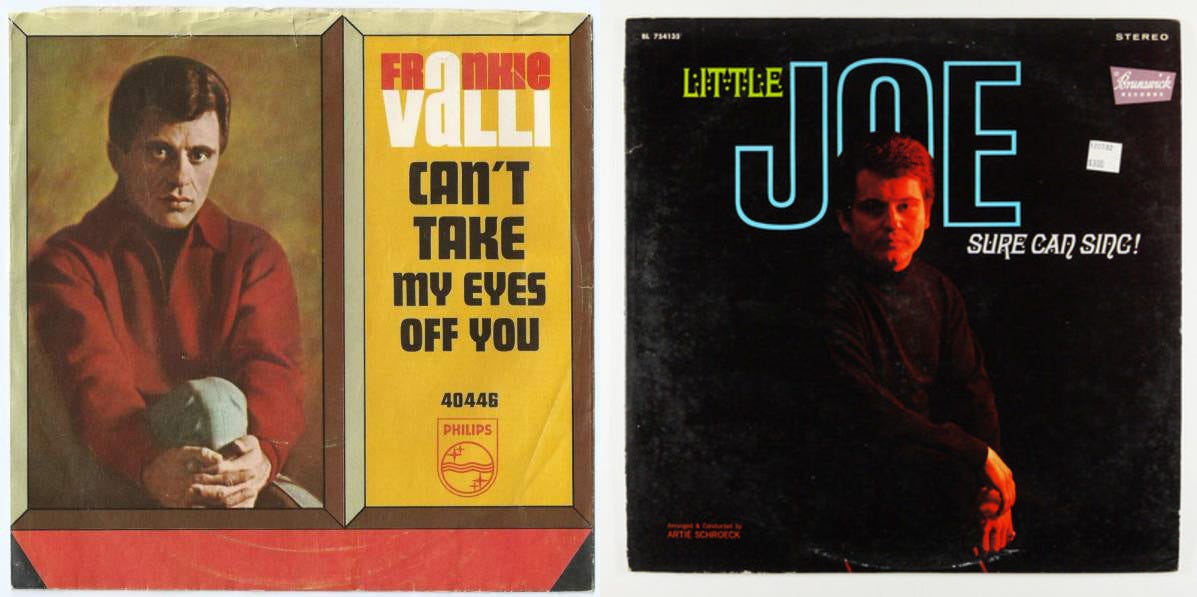

In 1968, in his mid-20s, Pesci finally got the chance to release his own album, Little Joe Sure Can Sing, under the name Joe Ritchie. According to the liner notes, Ritchie was discovered by a producer while singing in Harlem with a well-known jazz trumpeter. The Valli connection seems like a likelier origin story. The record seems designed to piggyback on the success of Valli’s solo single, “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” — they share a producer/arranger in common, and their covers are similar. Valli, on his, sits alone in a red sweater, staring at the camera with blazing intensity. Pesci strikes a similar pose in a constrictive black turtleneck, with a lightless expression that mainly communicates a discomfort with posing.

The genre is what we would now call easy listening. Pesci sings the day’s pop hits (Lennon–McCartney, the Brothers Gibb) in a self-serious, jazzy style that doesn’t sound much like jazz or like pop. His vocal style is directly cribbed from Scott’s, minus the facility or verve, so that Scott’s idiosyncrasies come off as technical failures and strange choices. Scott’s voice was languid, while Pesci’s sounds feeble; Scott would deploy a wide vibrato, whereas Pesci seems to crumple under the weight of a long note.

I like ephemeral ’60s schlock; I think the fanatical insistence on beautiful feeling can be a beautiful thing, and I’ve heard enough of it to know that this is not a good record. When I listen, the most poignant thing I hear is Pesci falling short of the artist he longed to be.

****

Fast forward another decade. Here we find Pesci, in his mid-30s, serenading tables at an Italian restaurant in the Bronx. He works as the manager here, and rents the apartment upstairs. He has retired from performing, outside of the singing maitre d’ routine, and even that doesn’t last long: “A couple of fights broke out,” he told Tom Snyder in 1998, “and I wanted to smack people with the guitar.”

There were moments, in the intervening years, when it seemed his career might really take off. In the early 1970s he toured the US as half of a musical comedy act, playing to audiences in the hundreds. “That life is a dead-end street,” his partner, Frank Vincent (later Phil Leotardo on The Sopranos), would tell the Times. “It’s sad. We didn’t think we could go to the next level.” After they split, Pesci was cast in a low-budget crime movie called The Death Collector, and decided to try his luck in film. “I came out to Hollywood,” he told Snyder. “I couldn’t get an agent. I couldn’t get arrested — well, I could have gotten arrested. I really couldn’t do well at all. I mean, I tried so hard.” After a while Pesci found himself in Las Vegas, according to the Tribune, digging ditches for $15 a day.

When Pesci talks about this period of his life, it’s not the professional disappointment he lingers on, but the toll of desperation itself. “It just takes the life out of you to some point that you wind up compromising so much,” he told the Tribune. “There was a point in my life I was trying so hard not to offend others in order to get a job. If I’d bump into a wall I’d say ‘Excuse me.’”

The actor languishing in a restaurant job is a cliche of failure. But in Pesci’s trajectory, this restaurant, Amici’s, seems like a small oasis: a place where he belonged, where his efforts were valued and his worth was never in question; where he found a steady paycheck and a source of self-respect. He was doing what he’d always done — entertaining people — but free of the albatross of ego.

By then, Jimmy Scott had lived through his own series of letdowns, which had led him back to his hometown of Cleveland. In 1963 he released a debut LP, Falling in Love Is Wonderful, recorded with Ray Charles for his label, Tangerine. The early response was ebullient, but the album was shelved when a predatory record executive claimed Scott was still under contract to his own label. Having spent his advance, Scott needed to find work: He took a job at a burger joint, then as a nurse’s aide at a convalescent home, then at a Sheraton hotel. Aside from the occasional singing gig, he’d live a quiet, working life for the next 25 years.

“In pressing questions about his reaction to this phenomenon, I look for signs of anger or bitterness,” Ritz, his biographer, writes. “I find none.” Of his restaurant job, Scott told him, “I see singing as public service work — you’re serving up entertainment — so serving food is related.” About the convalescent home, he said, “That work let me offer loving assistance to those in need. It gave me a special kind of peace.” In his free time, Scott turned to spiritual study, working toward a ministerial license while taking an interest in other religions. He fell in love and made a new attempt at building a family.

There’s no moral here. Scott had good reasons to be angry and bitter, and a different person might just as rightly have been. The parallel between Pesci’s and Scott’s disappointments is uneven: Being Black, with a body that didn’t resemble a norm of his gender, Scott faced far greater material obstacles than Pesci ever did. What seems most relevant here is Scott’s self-constancy: outside the arc of success he’d imagined and deserved, he always knew where to find himself.

“It goes back to this business of time,” he said to Ritz. “I saw it wasn’t my time. Mom used to say that God might not be there when you want him, but He’s always on time. I had one timetable that said my career would take off in the Fifties. When that didn’t happen, I had another timetable that said Falling in Love would kick-start my career in the Sixties. When that didn’t happen, I realized my timetable wasn’t the one that mattered. What was God’s timetable? I didn’t know, but to find out required patience. I’m not exactly sure what wisdom is, but I know there’s no wisdom without patience. Maybe wisdom is patience.”

One day, returning to work after running an errand, Pesci heard from an employee that Robert De Niro had called. “I said ‘Yeah, drop dead first chance you get,’” he told Snyder. “Because they used to call me ‘the actor,’ they had all these nicknames for me, so I thought somebody was just pulling my leg. But when I looked at the number — I just sidled over to the bar and took a little peek at it, without them knowing I was looking — I noticed that the area code was the correct area code for Los Angeles. And the dope that told me didn’t have the brains to know that.”

De Niro had seen The Death Collector on late-night TV, and thought Pesci would be perfect for the role of Joey LaMotta in Raging Bull. Pesci, over the phone later that night, told him he was retired, and that they should give the part to someone who’d appreciate it. De Niro was undeterred. That Sunday he arrived at Amici’s with Martin Scorsese, to bend his ear over dinner.

Pesci took the part, of course, but his reluctance was wise. He was trying not to get his hopes up, and to avoid backsliding into a mindset that nullified every satisfaction short of achievement. He might have been happy as a restaurant manager; happier, at least, than he’d ever be in Hollywood.

****

Rewatching Pesci’s Letterman interview, you realize his cigar is more than a prop — it gives his right hand something to do. The left hand searches for a task, stroking his chin, adjusting his jacket, scratching his thigh. Letterman’s rests calmly on the desk.

In less spectacular interviews, where Pesci is required to be himself, his nervousness is painfully bare. He takes questions at face value, giving dull, earnest answers and making no effort to be charismatic. He speaks too quietly, and his mouth is audibly dry. “When we see you onscreen in these roles, you are just such a loose cannon. I mean you are just exploding all over the screen,” said Bobbie Wygant in a taped interview from 1992. “And now you’re sitting as Joe Pesci and you’re hanging onto your chair for dear life.”

“I was watching myself the other night on a TV interview and I couldn’t relate to the person I was seeing,” he told the LA Times in 1991. “I didn’t know who he was! I relate better to the fictional characters in the movies I make because I spend all my time with them. This is a change in my life I don’t like at all.” A Baltimore Sun article from 1992 opens with Pesci stopping his golf game in sudden disorientation. “I didn’t know who the hell was about to hit that golf ball. Was it Leo Getz or David Ferry or Tommy or Harry or Joe. I’ve spent so much time as somebody else, and so little time as myself, I lost sight of who I was for an instant.”

This identity crisis would culminate in a strange artifact: a sophomore album, Vincent LaGuardia Gambini Sings Just for You, released unexpectedly in 1998. By then, Pesci’s acting career had quieted down; it might have been an attempt to recirculate the persona he’d established in the early ’90s, or it might have been the opposite — a death blow.

I find this album deeply embarrassing. It sounds to me like algorithmic nonsense, a strange jumble of lines and postures from his best known roles, delivered in a strange jumble of musical genres from salsa to Christmas music to rap. Gouged from a plot, this Pesci is hateful, and tactless. Nobody ever asked to hear Vinny Gambini call Mona Lisa Vito a “cunt.”

The album didn’t get much attention, outside a few biting newspaper reviews. Its lead single, a hip-hop track called “Wise Guy,” gained some infamy on MTV; I saw it once, late at night, and wondered for years if I had been dreaming. After that, Pesci stopped taking acting work. The early 2000s found him in West Village nightclubs, singing jazz under the name Joe Doggs.

****

After spending some time with Joe Pesci’s filmography, I’ve come to believe that his most definitive film isn’t Goodfellas or My Cousin Vinny, but rather 1982’s Dear Mr. Wonderful, his first starring role. It’s a quiet, independent film by German-Jewish director Peter Lilienthal, who had wanted to make a movie about the Jewish-American working class. Pesci plays Ruby, a lounge singer who runs a bowling alley in Jersey City, sharing a nearby apartment with his sister and nephew. He sings for patrons in the party room, over the din of nearby lanes, and dreams of making it big in Las Vegas.

The film struggled to find an American distributor (it was released here eventually, under the title Ruby’s Dream), and I can see why. It’s not a commercial film: hard to follow, with a script that totters between awkwardly lifelike and just awkward. It’s also hard to make sense of by American cultural codes. Primed on North American cinema, you’d expect a movie about a would-be Vegas lounge singer to dramatize his struggle to make it in Vegas. But it’s clear early on that Ruby will never “make it,” and that this doesn’t matter. Ruby has more mundane things to worry about: running a struggling business, providing for his family, keeping his head up. In an American movie, Ruby’s dreams would propel his escape from the banalities of real life. In Dear Mr. Wonderful, dreaming is the escape, a cherished hobby, and that’s good enough.

American fictions rarely distinguish between dreams and ambitions. Your dreams are what you strive toward; the further away you are, the more pitiable. This holds true for canonical films about artists, which tend to dramatize the struggle from nobody to somebody, or from somebody to nobody to somebody again. Think of Sunset Boulevard, A Star Is Born, Saturday Night Fever, or Amadeus, which would win the Academy Award for Best Picture three years after Dear Mr. Wonderful’s release. Nearly perfect, and deeply ideological, Amadeus trades in not one, but two narrative tropes about creative success, pitting them against each other: the tragedy of genius (doomed for self-destruction) and the tragedy of the mediocre (doomed to remain mediocre). The movie implies that the latter is worse. Being the best is the best thing to be; being the runner-up is worse than not even placing.

But Ruby’s dreams are not his ambitions. He is in his element before an audience of satisfied bowlers kicking back with a beer. Onstage he’s the master of ceremonies, performing the competence and control he lacks in his personal life. Offstage, he is the kind of guy who is always trying to help, whether or not his help is desired, or helpful. (“Throw it more in the middle,” he advises his love interest, as she attempts to bowl.) His goal is simply to be responsible, respected — a stand-up guy — but the bowling alley is being repossessed, and his nephew is falling into a life of petty crime. His failure is more painful for its ordinariness.

Pesci’s work on the film is masterful, and terrifically unflattering. “There are a lot of actors who can turn in incredible performances,” Howard Franklin, who wrote and directed The Public Eye, told the LA Times, “but they can’t resist telling you ‘by the way, this is technique — I’m not really like this.’ But great actors like Joe don’t leave any fingerprints on the picture.” There’s little melodrama in Dear Mr. Wonderful, no caricature, nothing to separate actor from character. When he sings onstage, you can see them merge. Pesci co-wrote the songs that Ruby performs, which are inadequate, but not comically bad; his singing is fine, just not good enough. He can’t quite hit the lower notes, and he can’t swing: his movements are emphatically on-beat, and his eyes search the audience for evidence that he’s doing it right. It’s never clear whose shortcomings are whose.

In the movie’s most dramatic scene, Ruby’s idol, Tony Martin, shows up unannounced to hear him sing. Ruby is beside himself. He shouts him out from the stage, and dedicates the next song, an original composition, to him. But Tony has a plane to catch, and he wants to get some bowling in beforehand. He stands up to leave before the first chorus, blowing Ruby a kiss on his way out the door. Of all the standout scenes in Pesci’s repertoire — all that brutality and tension — I find this one hardest to watch. It’s also, I think, his greatest moment as a performer, and the closest he ever got to channeling his idol — conveying absolute meekness with total control.

****

For a while when I was a kid, my father was out of work. One day he got a call from some scam operation, claiming to be, as I recall, a sort of average-joe modeling agency that placed ordinary people in catalogues and the like. My dad is not the kind of person to fall for something like that, but I guess his job search wasn’t going so well. On a summer afternoon, he handed me a camera and told me to take some pictures of him out on the balcony of our apartment. He leaned against the railing and grinned in the sunlight.

These pictures are stowed away somewhere. I still come upon them sometimes. For years I found them very difficult to look at. There’s no tragedy here: He got a job eventually, and in the meantime we didn’t starve, didn’t get evicted. My mother was working steadily. What pained me was just the fact of being embarrassed, not by his unemployment, but by what seemed at the time like a lapse of character.

There was a time when I was afraid of having to witness a partner struggle. I would have preferred some form of hardness and cruelty to softness, if softness made me feel pity (I’m sure that most of my partners would have preferred that, too). The issue, of course, was my own fear of failure, which was my prime motivator until those fears came to pass. Failure is relative, mind you. I’ve done just fine. But I’ve become someone I feared becoming when I was young, inexperienced and unforgiving. I’ve been the struggling partner who hates the person they’re behaving as, who can’t seem to pull themselves out of a spiral, who feels doubly ashamed of the way they see themselves seen by loved ones.

Now, when I think of those photographs of my dad, my heart feels full, my love for him very acute. There’s an intimacy in the dynamic that produced them that is closer to what I now understand love to be. Back then I flinched at his vulnerability, but I got to know him better through it. Having known him a lot longer now, my concept of “dad" has a basic integrity that accommodates vulnerability and hardness, difficult moments and tender ones, and I think that is one definition of love, a constant impression through infinite variations.

My initial attraction to Joe Pesci owed to the fact that he never made me uncomfortable. Once I got to “know” him better, I found he was capable of making me more uncomfortable than most actors ever have. It takes a lot of courage to appear so meek, and courage is attractive; but more than that, I find his meekness is context for his hardness and disinterest, that the two coexist in a character whose fullness is very romantic. As a romantic, I think the ultimate love is to know someone so well that you know you’ll never know them completely. What sustains an attraction is the potential those unknowns contain.

A couple of years ago, Pesci came out of retirement for Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, playing a soft-spoken mob boss who rules with gravitas instead of brute force. It was his first major part in a decade — in a poetic reprisal, De Niro reportedly had to ask him 40 times to agree to appear — and it seemed as though he had mellowed with age. Like many viewers, at the time I was surprised that he could pull off such an understated performance. Having filed him away as an archetype of himself — “Pesci” is a tiny, but foundational part of what I know the world to contain — I was excited by a sense that the world I’d taken for granted was transforming slightly, and a new avenue was opening in my memory. There is nothing more romantic than the possibility of being surprised.

Pesci didn’t bother much with press for the movie, so we don’t know how he assessed his own work. I suspect he was proud of himself, but that he took much more pride in a parallel achievement, which slipped unnoticed amid the hype. Two days after the movie’s Netflix debut, Pesci released an album, Still Singing, the first to carry his own name. “This record took many years to come to life and has become a tribute to my longtime friend Jimmy Scott,” he announced in a statement. “Thank you all and enjoy.”

Jimmy Scott had passed away five years earlier, in 2014. In later years, he’d finally gotten something closer to his due. In 1991 he was asked to sing at the funeral of an old friend, the songwriter Doc Pomus. Seymour Stein of Sire Records was in attendance. He was blown away, and signed him shortly thereafter. The album that followed, All the Way, received rave reviews and a Grammy nomination. Scott would record nine more, singing for star-studded rooms and appearing on soundtracks for major Hollywood movies. He even made an appearance in the Twin Peaks finale. (“I didn’t quite understand the storyline,” he told Ritz. “David had me wearing a bowtie and singing to a dwarf.”) He would never sell a million records — as Ritz notes, his style was always too singular — but he toured the world for years afterward, reviving an old, adoring fanbase and solidifying a new one.

Pesci and Scott would reunite, to duet on “The Nearness of You,” for the album and documentary I Go Back Home, just before Scott’s death. You can watch a snippet from the recording session on YouTube: Scott, then in his 80s, sings from a chair, looking frail but soaring into the high notes. Pesci crouches reverently at his side. “If you’re only half-listening you might not even notice where one begins and the other ends,” the music journalist Richard Williams wrote.

On Still Singing, Pesci sounds somehow more like his idol and more like himself. His style and technique have met their potential: he now has the stamina to support his own voice, which has always been richer and more textured than I ever noticed; and the self-possession to be gentle.

The album received muted praise, relative to the film he was promoting. Pesci’s a lovely singer, and the album is good, but it’s not a work of genius. Given the choice, you’d be much better off listening to the reissue of Falling in Love Is Wonderful, a statement I don’t think Pesci would dispute. It’s a minor accomplishment by the standards of Pesci’s career: a good homage to a great artist. But that makes it, in a way, more significant than anything else he’s ever done. It fulfills a lifelong aspiration, to sing like Jimmy Scott.

A joy to read! Looking forward to more CM

Ask Joe about his insider trading days with Mitchell Stein. Then you'll have the complete bio.